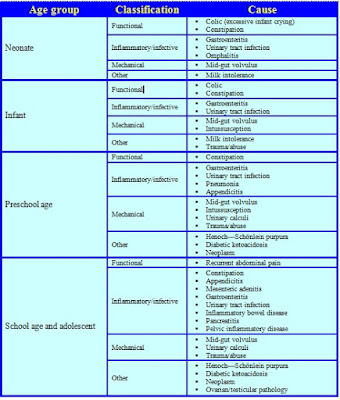

Causes of abdominal pain in childhood Abdominal pain is one of the more common reasons for parents to bring their child to the Emergency Department. While many diagnoses traverse all age groups, some are more age specific (Table 1).

Assessment of abdominal pain

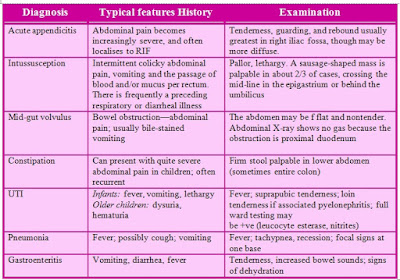

The assessment of the child with acute abdominal pain depends on a good history and careful examination. The nature of the pain itself must be carefully elicited, including its characteristics, relieving and precipitating factors. Truly severe colicky pain suggests an obstruction of the gastrointestinal, genitourinary or hepatobiliary tract. Pain can be referred from elsewhere such as the testes and the lungs. Associated features must also be elicited such as gynecological symptoms in adolescent girls. A full and careful but sensitive examination must follow. If acute activity precipitates pain, it suggests peritonitis. Acute serious problems need rapid combined surgical and medical assessment and management. The algorithm (Table 1) may be used as a guide to the systematic consideration of various categories of causes of acute abdominal pain. Typical features of some important causes of acute abdominal pain in children are described in the following table (Table 2).

Notes:

• Acute appendicitis must be considered in any child with severe abdominal pain, aggravated by movement such as walking, or a bumpy car ride. The child is often flushed, with a tachycardia and a mildly elevated temperature. In the very young child, in whom the risk of perforation is higher, the presenting symptoms are less specific. The diagnosis is clinical—no laboratory or radiological tests are required, although there is usually an elevated white cell count.

• The peak age for intussusception is 6–12 months. The child may present in shock. Plain anterior chest X-ray may show signs of bowel obstruction, with decreased gas in the right colon. The diagnosis is confirmed by air insufflation or barium enema, with reduction usually possible by the same means (unless there are signs of peritonitis, which increase the risk of perforation).

• Mid-gut volvulus is commonest in the newborn period, but can occur in later childhood. Predisposing factors include malrotation and abnormal mesentery.

• Vomiting is rarely due to constipation.

• Some children suffer recurrent non-specific abdominal pain, with no organic cause identifiable. Constipation is often an important contributing factor. Psychogenic factors (e.g. family, school issues) need to be considered. These children should be referred for general pediatric assessment.

• Some less common diagnoses need to be considered in patients with certain underlying chronic illnesses. Hirschsprung disease can be complicated by enterocolitis, with sudden painful abdominal distension and bloody diarrhea. These patients can become rapidly unwell with dehydration, electrolyte disturbances, and systemic toxicity, and are at risk of colonic perforation. Primary bacterial peritonitis can occur in children with nephrotic syndrome, splenectomy and those with VP shunts.

|

| Table 1. Causes of abdominal pain by age |

|

| Table 2. Assessment of abdominal pain in pediatric |

Management

An algorithm for abdominal pain management is given in Table 1.

Intravenous access should be established. The electrolytes should be measured in a child who appears dehydrated and blood and stool cultures obtained if the child is potentially septic. The patient should be given and fasted until a surgical opinion has been sought. In addition, a nasogastric tube will be needed if there is bowel obstruction.